Find the Why: Uncovering the (Sometimes Hidden) Reasons We Do the Things We Do

Underneath the things we do, there are almost always deeper reasons. In order to make the best decisions and live the best life, we should figure out what they are.

In some of my previous posts, I use the phrase “Find the Why” as a kind of shorthand for the process of digging deeper into our behaviors, feelings, and ideas to figure out what’s really going on: how we react to events, the way we behave at work and with friends, our fears and habits and vices — all of them have an underlying Why.

In this post, I want to unpack what I mean by that, and offer up a framework for Finding the Why on your own. This is a framework we can use to build a deeper understanding of why we are the way we are. (And, hopefully, a process by which we can be more certain that problems are solved for realsies.)

When we Find the Why, we take back control of our behavior.

Why Is Finding the Why Important?

Not too long ago, I was in a retrospective for a project, and there were a few things that had just plain failed to work. After collecting everyone’s opinion on what went wrong, I started asking why things went wrong.

Someone interrupted me and said, “It doesn’t matter why it went wrong; we need to focus on how we’re going to fix it.”

In certain circumstances, I can see the point: if your pants are on fire, you should focus on putting them out, not asking whether they started burning because you are, in fact, a liar liar.

The problem with only solving the problem, though, is that problems are often just a symptom of something deeper. If I put out the fire, but don’t ask why it started afterward, what’s to stop me from hanging my pants over a scented candle to “freshen them up” again?

If we don’t understand why the problem occurred, we have no way of knowing if our fix has actually solved the problem, or just temporarily covered it up.

How Will Finding the Why Make Life Easier?

By taking the time to examine the underlying causes of problems, we gain subtle but extremely powerful advantages.

We become proactive instead of reactive.

There are a few people I work with on a daily basis who stress me out just to be around. Their entire existence, as far as I can tell, is spent careening from one fire to the next, desparately trying to stay on top of an endless stream of fire drills.

This is a reactive approach, and it’s basically a waking nightmare: the world is constantly happening to you. Chaos reigns, and every problem is a surprise.

Living reactively is like an endless game of whack-a-mole where you’re the one taking all the lumps.

If, however, you take a proactive approach, life starts to look a little different: because you’re making the effort to understand why problems are occurring, you start to see patterns. Problems that previously felt novel start to resemble each other, and you can apply your previous experience to help solve new problems more effectively.

The biggest advantage to a proactive approach is that your deeper understanding allows you to see problems before they happen: because you’ve worked out the underlying cause of previous issues, you can spot potential problems early — and correct them before anything breaks.

We can find patterns that make problems easier to solve.

By thinking through to the deeper causes of our problems, we can start to see that a whole lot of problems share similar root causes.

Part of my job is building processes and tools to make teams more effective. When I first started looking at the bottlenecks and time drains our teams were up against, they seemed like unrelated challenges — this made it feel like the effort was doomed.

After taking time to Find the Why, however, we found a few common culprits:

- There was a lack of clarity about goals, so teams were being forced to make educated guesses about what was expected of them.

- People were being asked to do things that fell way outside of their job descriptions and/or comfort zones.

- Many core pieces of information were completely undocumented, meaning teams had to wait for the one or two people who understood it to have time to help them.

These three problems were causing the vast majority of the bottlenecks, performance problems, interpersonal conflicts, and other issues we were trying to solve. By realizing this, we were able to focus our efforts in a way that actually made an impact.

Had we instead looked at these as unique technical, tooling, and interpersonal problems, we would have wasted a huge amount of effort treating the symptoms — and wouldn’t have made much progress.

Sometimes noticing is all it takes.

When people start working with nutritionists or dieticians, a really common first step is to ask them to write down everything they eat throughout the day. And in many cases, this simple act causes people to make improvements in their diet.

I ask something similar of myself and the people I coach: take note of where your time goes during the day.

When we’re paying attention, we tend to make better choices.

If we take the time to Find the Why behind our problems, we’re able to notice when something has the potential to become problematic.

If you’ve ever burned out an electric motor, you probably now know that there are certain sounds and smells that mean something’s about to go horribly wrong. By recognizing that, you’re able to turn off the machine before an expensive failure happens.

Sometimes paying attention is all it takes to eliminate problems.

How Do You Find the Why?

As with most things, there’s no foolproof formula or ironclad process; every situation will vary in subtle ways, so coming up with a universal solution is impractical. However, there are some general guidelines that will make it easier to Find the Why in most situations.

1. When you notice a problem, pause and assess the situation.

At arm’s length, this may seem like an obvious statement, but it’s important to keep in mind that we exist in a culture of self-destructive work ethic and unhealthy commitment to our own ideas: when we’re in the middle of a project, our instinct may be to just power through.

When you hit a wall, sometimes it makes sense to plow through it. But most of the time there’s a solution that hurts less.

Before you put your head down and try to smash it through whatever the problem is, take a beat and try to get a sense of what you’re up against.

2. Try to see the whole picture.

While assessing the problem, try to spot all of the symptoms: is there just a puddle on the floor? Or is there a leak in the ceiling, too?

A broad understanding of everthing that’s going wrong provides a more complete context for problem solving. Making decisions with incomplete information will likely lead to incomplete solutions.

3. Think about why it happened.

It’s tempting to stop at the symptoms: “Why did I snap at my friend today? Because I was having a bad day.”

Having a bad day is a symptom of something. Why was it a bad day? Did something happen? Am I frustrated? Is there something common in all of my bad days?

Digging beyond the symptom can help us recognize the cause, which is what we need to address if we hope to fix the symptom permanently.

4. Ask “Why” again.

If you asked Taiichi Ohno how to Find the Why, he’d tell you to ask “Why?” five times to make sure you’ve reached the root of the problem:

- Why was the project late? The team couldn’t deliver on time.

- Why couldn’t they deliver on time? There were last-minute changes to the deliverables.

- Why were there changes to the deliverables? Management was undecided about what to prioritize.

- Why was management undecided? There was a lack of clarity about what should be built.

- Why was there a lack of clarity? The team wasn’t included in the planning process.

In this example, what initially looks like a performance problem (missed deadlines) may actually be caused by poor communication and planning.

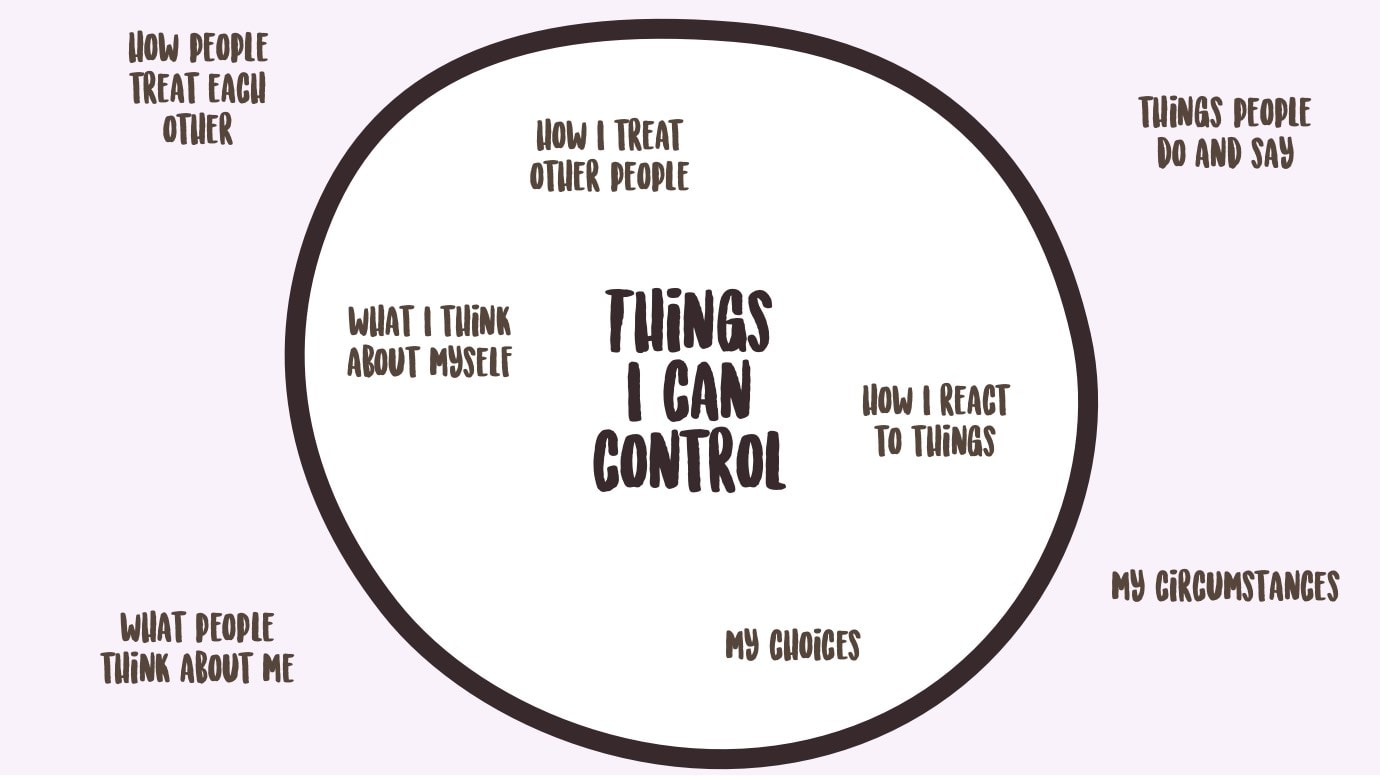

5. Keep asking until you’ve reached the deepest reason you can control.

Going back to the example where I’m having a bad day, maybe I find a chain of causes like this:

- I’m having a bad day.

- Why? I feel like I wasted the whole day.

- Why? I didn’t accomplish any of my tasks.

- Why? I spent the whole day in meetings.

- Why? People keep inviting me to meetings.

In this chain, the cause of my grumpiness is that I feel like I lost the whole day to meetings. The final cause — that people keep inviting me to meetings — appears to be the root cause, but it’s beyond my control: I don’t control other people, so how can I stop them from inviting me to meetings?

If I take one step back, however, I showed up to those meetings. This is within my control, so I can ask a new set of questions:

- I spent the whole day in meetings.

- Why? Because I had a buttload of meetings on my schedule.

- Why? Because I accepted every meeting invite, even if they were irrelevant to my work.

- Why? Because I didn’t want to seem rude by declining.

Now that I’ve explored this new line of questioning, there’s a new potential root cause: I’m accepting meetings even when I shouldn’t be.

This means I’m no longer helpless; I can control the way I respond to irrelevant meeting requests.

If we dig too deep, we end up with problems that are either so broad they’re not solvable in a reasonable time frame, or that extend beyond what we’re able to control, which removes our ability to solve them entirely.

We need to Find the Why at the deepest level we can control. This way, we can come up with a solution and actually implement it. Because — remember — no one is coming to save us.

Life Is Easier When We Know Why

Even though it can be frustrating, stressful, or even frightening to Find the Why, there have been few things that improved my life more dramatically than adopting this as a core strategy for being alive.

If something makes me angry or sad, digging deeper helps me find a healthy and/or productive way to process that emotion. If I’m stressed and irritable, I can dig deeper and figure out where that stress is coming from and how to address it. If something goes wrong at work, I look for deeper patterns that will prevent it from ever happening again, rather than just putting out the fire and pointing fingers at someone else.

After I learned to Find the Why, I became a happier, healthier, less volatile person. (Or, as many of my friends would put it: “He’s less of a dick now.”)

If you put this into practice, maybe your friends will think you’re less of a dick, too.

And that’s a worthy goal if ever I’ve heard one.